NLP Strategies

Behind every human behavior are strategies that guide and control it. In NLP, methods have been developed that allow you to learn the strategies of experts, such as the creativity strategy of Walt Disney. In this way, motivational, learning, sales, and decision-making processes can be optimized.

Table of Contents

- What are Strategies?

- Walt Disney Strategy

- The TOTE Model

- NLP Notation

- Eliciting a Strategy

- Conditions of Structural Well-Formedness

- Installing a Strategy

- Examples of Strategies

- Flexibility Strategy

- Love Strategy

- Decision Strategy

- Utilization of Strategies

- Planning Context Markers and Decision Points

- Streamlining Strategies

- Redesigning a Strategy

- Installing with Anchors

- Interrupting Strategies

- Sources of Error when Installing a Strategy

What are Strategies?

Strategies are the ways in which we organize our thoughts and behaviors to accomplish a task.

There are so-called macro and micro strategies. For example, if someone sets out to become a successful sociologist, their macro strategy would be the step-by-step construction of that career: studies, Ph.D. with honors, publications, professorship, etc.

The micro strategies would refer to how that person learns, writes, or presents themselves efficiently. These micro strategies can be analyzed as specific sensory sequences. They describe an internal processing of perceptions, meaning strategies are formal structures independent of content.

Each strategy also includes specific beliefs and attitudes, such as “Being successful is possible for me” or “I have the ability to achieve this goal.”

Strategies are like recipes: ingredients (representational systems), quantities (submodalities), and sequence (order of steps) are crucial. Change the order and you change the result.

In NLP, we analyze strategies to discover what people do when they succeed so these patterns can be modeled and taught to others. Thus, strategies are a fundamental part of modelling.

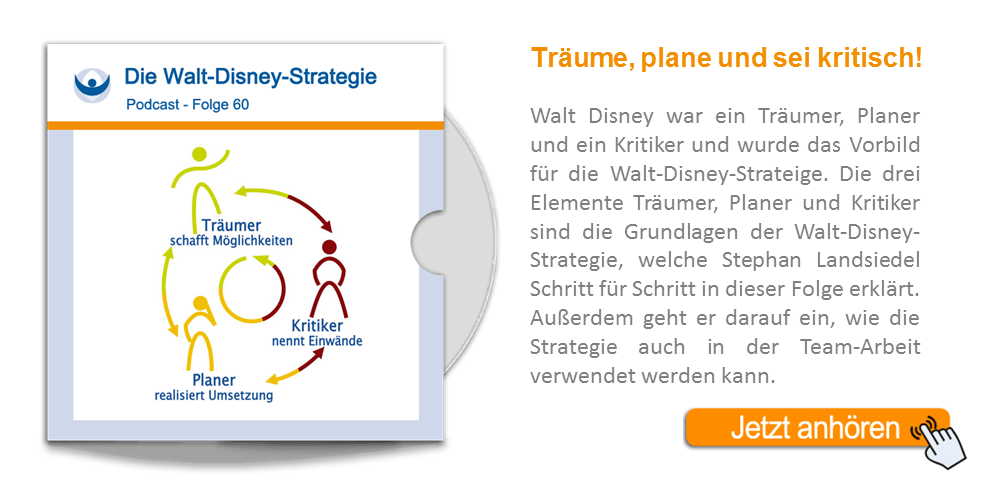

Walt Disney Strategy

The Walt Disney Strategy describes goal creation through three roles: the dreamer, the realist (planner), and the critic. It provides a structured framework for creative thinking and project realization.

The TOTE Model

The T.O.T.E Model (Test – Operate – Test – Exit) illustrates the cognitive process of learning and behavior correction. It describes the loop humans use to reach goals through continuous feedback and adjustment.

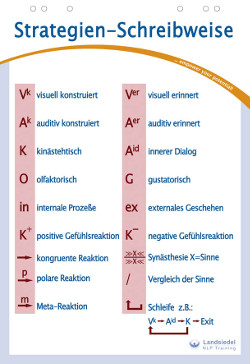

NLP Notation

Representational Systems

V: Visual (seeing)

A: Auditory (hearing)

K: Kinesthetic (feeling)

O: Olfactory (smelling)

G: Gustatory (tasting)

Superscripts

e = remembered

k = constructed

in = internal

ex = external

Subscripts

+ = positive

- = negative

Examples

Aex: auditory external

Ain: internal dialogue

Kex: physical sensation

Vk: visually constructed image

→ = leads to / = simultaneous visual & auditory perception

Example: Vin → K+ → Ain → K-

Translation: An internal image (me on a beach) creates a pleasant feeling, followed by a negative inner dialogue (“I have no time for this”), resulting in frustration.

Eliciting a Strategy

Person A is the model, B asks the questions, and C observes and takes notes. The goal is to uncover the sequence of sensory representations (VAKOG) and decision points used by A in performing a specific skill.

Overview

- Preparation

Guide A into the experience and set the framework for questioning. - Gathering Information

Find the main structure of the strategy, ask about sensory details, and identify related beliefs and submodalities. - Summarize and Verify

Ensure all essential elements are captured and accurate.

A. Preparation

- Lead the person to recall the experience you want to analyze — e.g., making a decision, feeling motivated, being creative, etc. Have them relive it as if it were happening now (using VAKOG cues).

- Clarify the context for questioning, e.g., “If I had to replace you for a day, how would I need to do it to perform this task as well as you?” Maintain rapport throughout.

B. Gathering Information

- Focus on process rather than content.

- Identify the overall sequence first, then the detailed steps.

- Use meta-model questions to elicit specific sensory details.

- Observe eye movements, breathing, tone, and gestures.

Sample Questions for Unpacking a Strategy

Trigger (Start of the Strategy)

- “What happens first?”

- “How do you know it’s time to begin doing X?”

- “What do you see, hear, or feel right before you start?”

Process (Operate Phase)

- “What happens next?”

- “How do you do that exactly?”

- “Do things happen one after another or simultaneously?”

Completion (Test / Exit)

- “How do you know you’ve finished?”

- “What lets you know it worked?”

- “What happens if it doesn’t feel complete yet?”

C. Identifying Beliefs and Submodalities

Each strategy involves beliefs and submodalities that determine its effectiveness. For instance, a person with a strong decision strategy might believe, “I always choose correctly.”

Questions to elicit beliefs:

- “What would I need to believe to do what you do?”

- “What thought is essential when you perform this successfully?”

- “What makes you sure this will work?”

Conditions of Structural Well-Formedness of Strategies

A. The strategy must have a sensory-specific goal.

It should include a clear sensory representation of the desired outcome and a feedback mechanism for testing progress.

B. The strategy must involve all three major representational systems (V, A, K).

Each representational system processes information differently, contributing unique data for effective decision-making.

C. The strategy must include a decision point before returning to the starting point.

- Every loop must have an Exit condition; otherwise, the process may repeat endlessly.

- Avoid two-point loops (e.g., bouncing between visual and kinesthetic without an exit).

- To stop loops: use counting, time limits, or sensory shifts to force a decision point.

D. The strategy should include an external check after a certain number of steps.

External feedback ensures that the process stays aligned with real-world data and results.

Installing a Strategy

Installing a strategy means transferring a specific sequence of thought and behavior to someone who does not yet have it, so that it becomes available to them automatically in the right context.

- Using Chain Anchors — link sensory anchors to each step of the strategy sequence.

- Conscious Rehearsal — practice performing the sequence with appropriate physiological cues (e.g., eye movements, breathing, tone).

- Interrupting Old Strategies — break entrenched patterns by overloading or confusing the system.

Examples of Strategies

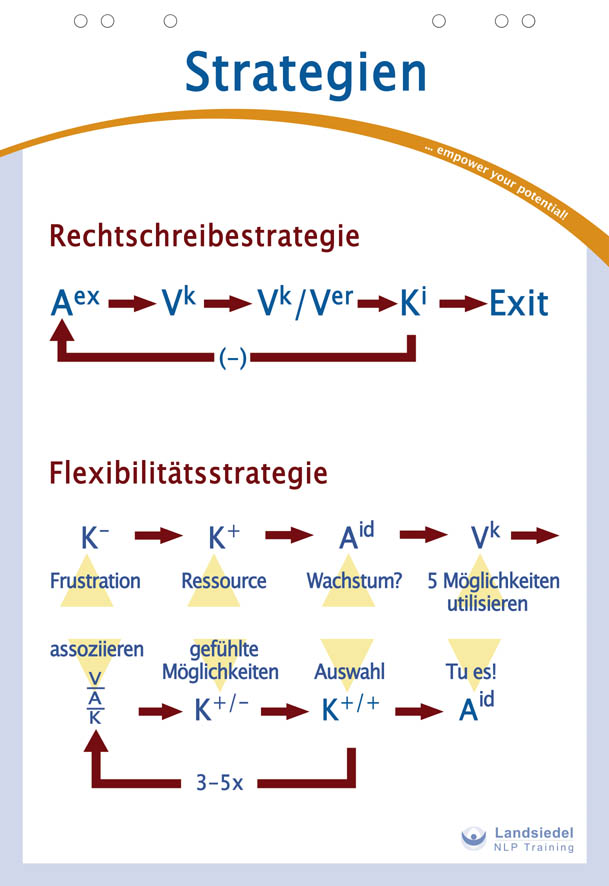

Spelling Strategy

- (Test) The person hears a word (auditory external input).

- (Operate) They construct a visual image of the word.

- (Test) They compare that visual image to one stored in memory (visual remembered) and generate a kinesthetic feeling of congruence or incongruence.

- (Exit) If congruent, they write the word; if not, the process repeats with adjustments.

The optimal spelling strategy is a two-step visual-kinesthetic process: visualize the correct word and then feel whether it “looks right.” Poor spellers often rely on inefficient auditory (letter-by-letter) strategies. Installing the V/K pattern allows faster and more reliable spelling.

Flexibility Strategy

- Identify a typical situation where flexibility would be useful.

- Anchor the starting state (e.g., frustration).

- Recall a time you approached challenges creatively and anchor that state (e.g., curiosity, excitement).

- Chain the two anchors so that the positive state follows the negative.

- Ask: “What can I do now to handle this challenge creatively?”

- Visualize five possible options, experience them fully (VAK), and choose the one that feels most empowering.

Love Strategy

Can you remember a time when you felt truly loved?

Step back into that moment and relive it. Then identify what triggered that feeling:

- V — What did your partner do or how did they look at you?

- A — What did they say or how did they say it?

- K — How did they touch or physically connect with you?

By exploring submodalities, you can determine precisely which sensory cues produce the emotional experience of love and congruently reproduce them.

Decision Strategy

Choosing from a menu is a simple example of a decision strategy. The quality of our decisions depends on how effectively we generate, represent, and evaluate alternatives.

Common Problems with Decision Strategies

- Generating Alternatives:

Too few options, or looping endlessly without reaching an exit. - Representing Alternatives:

Not engaging all representational systems; insufficient data; unrealistic comparisons. - Evaluating Alternatives:

Inappropriate or conflicting criteria, or comparing options inconsistently.

Utilization of Strategies

Utilization means applying an existing strategy that has already been elicited. The NLP practitioner aligns communication or task framing with the client’s internal sequence to evoke resourceful states.

Exercise

- Elicit a creative strategy from someone by identifying their internal process during creativity.

- Identify an area where they feel blocked.

- Guide them through the creative sequence while they imagine the problem situation, generating new options automatically.

Planning Context Markers and Decision Points

When a strategy is useful in one context but not another, a decision point or context marker must be installed to signal which strategy fits which situation. Without it, both may trigger simultaneously, causing confusion or paralysis.

Streamlining Strategies

Streamlining simplifies strategies that are overly complex or inefficient. Example: In reading, some people subvocalize each word (A-d step), while speed readers go directly from seeing the word to understanding (V → K). The goal is to shorten the loop for efficiency.

Redesigning a Strategy

To redesign a strategy, determine:

- What information (input/feedback) is required in which representational systems.

- What distinctions and associations are needed for processing.

- Which operations and outputs must occur to reach the goal.

- What is the most efficient and effective sequence for these steps.

Installing with Anchors

Anchoring links internal representations to external or internal triggers. During installation, you anchor not the content but the use of specific representational systems, establishing quick access to the new sequence.

Example

Anchoring a motivation strategy: Have the client recall a time they successfully motivated themselves, identify the sequence (e.g., V → A → K), and anchor each step kinesthetically. Then fire the anchor when the person faces a new, unappealing task to trigger the same strategy automatically.

Interrupting Strategies

When a strategy is deeply ingrained but produces unhelpful results, it can be interrupted through:

- Overloading – introducing too much sensory input to continue the loop.

- Redirection – shifting focus to a different sensory system or context.

- Spinning Out – looping the sequence on itself until it collapses naturally.

Sources of Error when Installing a Strategy

- Poor calibration — not detecting subtle state changes.

- Unclear transitions between steps.

- Lack of congruence or conflicting anchors.

- Missing elements of well-formedness.

Deutsch

Deutsch English

English Français

Français 中文

中文 Español

Español नहीं

नहीं Русский

Русский