Perception & Perceptual Filters

Perception

We can only use information in communication that we have received. This is only possible with open senses. If our perception is blocked, our communication cannot flow.

Four Simple Facts About Our Perception

(taken from an introductory lecture in Psychological Physiology)

- We do not perceive reality as it is. (Transformation in the sensory organs)

- Only a small part of reality is perceptible to us (X-rays, infrared light, etc. – animals can perceive that)

- Of the processes for which we have sensory organs, only those that reach a certain strength become conscious (different pain perception)

- The processes that we become aware of are perceived only roughly in their variety. (Experiment: Weber’s difference threshold)

There is also a 75-minute recording on this topic available in our online academy that you can watch in full length right now. Just click the “Watch Video” button to learn more.

How Our Perception Works

(taken from "The Reality of NLP" by Alexa Mohl)

In school, we learned that the eye works like a camera. Light rays from objects in our environment create sharp images on the retina at the back of our eyes. From this, we concluded that we all see the same thing—the reality around us.

This idea of seeing as a camera-like process is wrong. Seeing does not work like a camera. The surrounding reality does not create images in our eyes that are sent to the brain. Therefore, we cannot assume that we all see the same thing and share the same reality.

We could have noticed that something was wrong even in school. I remember asking why we see things upright when, if vision worked like a camera, images should appear upside down. The teacher’s brief answer was: “The optic nerve turns it around!”

What we learned in school no longer matches modern neurophysiological research. Seeing does not work like a camera. Reality does not form pictures on the retina that are transmitted to the brain.

What we create images of reaches our eyes as physical waves. In the cells of the retina, chemical processes occur, stimulated by these light waves, and enter the central nervous system as electrical impulses. Our brain processes these impulses into inner images. As with seeing, so it is with the other senses: environmental influences stimulate our sensory organs, which activate our brain. This brain activity, still not fully understood, produces what we call our world—the images we see, the sounds we hear, the textures we feel, and the things we smell and taste.

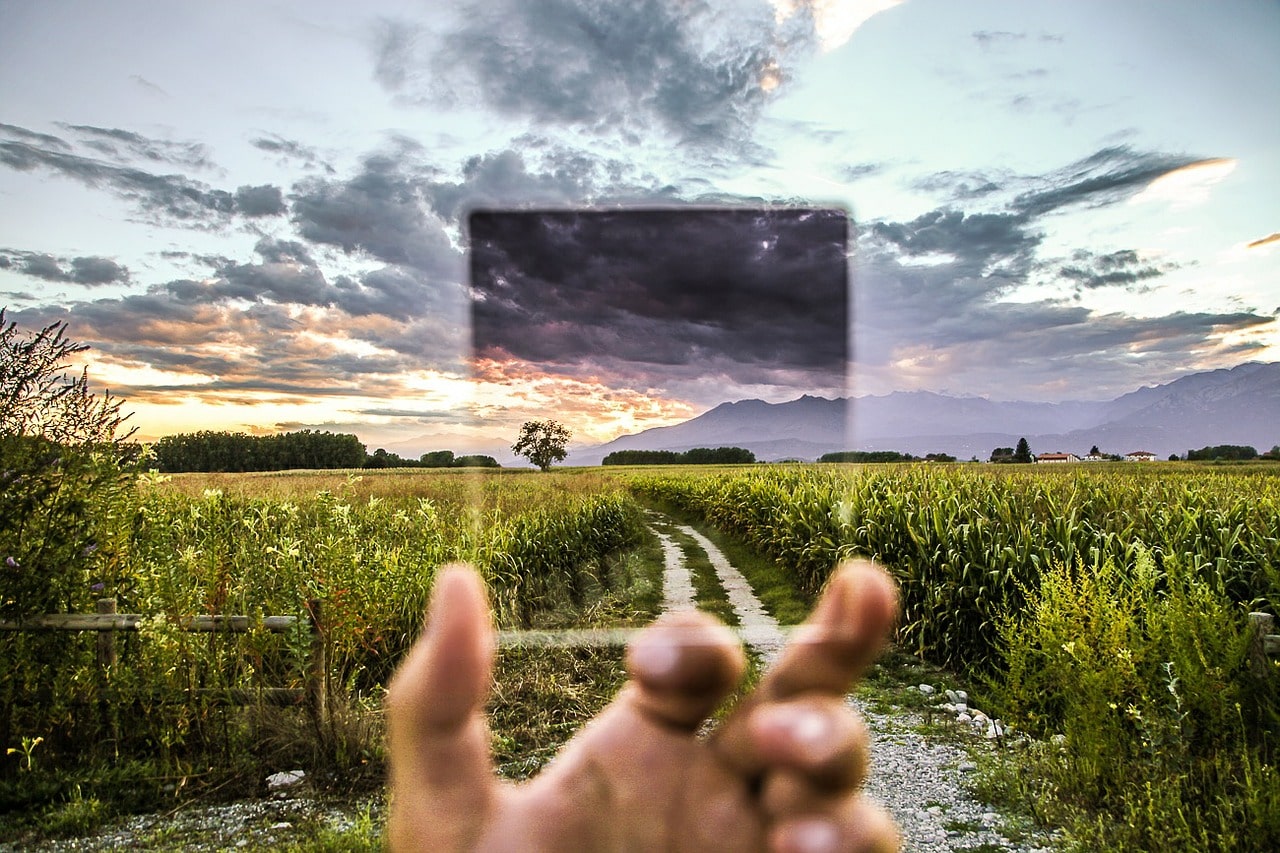

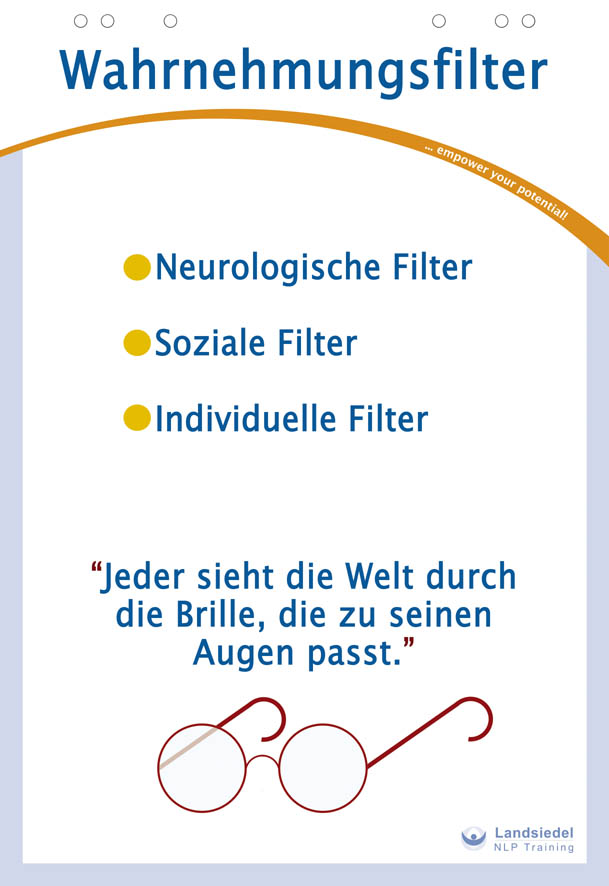

Perceptual Filters

We perceive the world through our five senses: we see, hear, feel, smell, and taste, taking in an incredible amount of information. We also represent our sensory perception linguistically. We use expressions referring to the visual, auditory, or kinesthetic sensory systems.

Neurological Filters (limitations of sensory perception due to nerve cells):

There are many physically measurable phenomena that we cannot perceive due to our neurology, such as specific sound frequencies or light waves that are significant for other living beings (e.g., dogs, bats, tomatoes). Our sensory perception is therefore subject to physiological limitations—certain information is not even registered by us.

Cultural and Social Filters (limitations of perception due to upbringing and society):

Our perception is also shaped by cultural and social patterns. The five senses of an Australian aborigine certainly deliver different information than those of a New Yorker. How many words for snow can we think of? Three, four, five? Eskimos know and name over 20 types of snow! In the Congo, perceiving spirits is accepted—in our society, it’s not. In the Congo, spirits are real; in our society, they are “ghosts.”

That means: even with the same neurology, perception of the world can differ greatly depending on the environment and traditions.

Individual Filters (limitations of perception due to personal experiences):

Similar to cultural filters, individual filters operate based on personal experiences. We privilege certain categories of information while ignoring others. Our ability to filter out unwanted input is clearly seen in the so-called “party effect”—the ability to hear one’s name across a noisy room while ignoring all other sounds.

Another example: one person enjoys identifying motorcycle engine sounds by brand because they love bikes, while another hears the same sound as noise pollution. Statements like “Nobody ever helps me” or “Everyone admires me” illustrate another form of selective perception.

The Fundamental Processing Processes

Generalizing, Deleting, and Distorting

Above, we saw the factors influencing our perception and the creation of our “map of the world.” Through language, we can convey our perceptions to others. Our way of speaking reflects not only our worldview but also the processes by which we construct it.

There are essentially three processing mechanisms through which we experience and linguistically represent the world: generalizing, deleting, and distorting. These allow us to survive, grow, learn, and make sense of the richness of the world. However, they can also cause problems when we mistake our selective perception for objective reality.

Through generalization, we learn to navigate life. For example, if as a child we once burned ourselves on an iron, we generalize that experience to all hot, similar-looking objects—we don’t need to repeat the experience.

An example of a limiting generalization is a dog phobia: being bitten once by a dog leads to fear of all dogs, restricting everyday life.

The ability to delete allows us to focus on relevant information; otherwise, we would be overwhelmed. For instance, someone can read a book while others talk around them.

Deletions become limiting when we ignore useful experiences, as seen in complaints like “I never get any recognition.” Such statements erase not only experiences of recognition but also who gave it and for what.

The third process, distortion, allows us to reshape and reimagine our experiences. This ability enables us to turn dreams into reality, paint pictures, or write novels.

The downside of distortion shows up in phrases like “I regret my decision.” Here, a process—deciding—has been frozen into a static event, depriving the speaker of control by redefining it as unchangeable.

Would you like to learn more?

Here you’ll find more exciting articles:

Deutsch

Deutsch English

English Français

Français 中文

中文 Español

Español नहीं

नहीं Русский

Русский