Metaphors

Metaphors have an incredibly important role in communication and in our own understanding.

Since ancient times, metaphors have been used as tools for teaching and transforming ideas, perceptions, and attitudes toward life.

Table of Contents

- Introduction and Function

- Important Principles of Metaphors

- Metaphorical Solution

- Construction of Metaphors

- Avoiding Misunderstandings in Metaphors

- Exercise for Developing Metaphors

- Symbols for Metaphors

- Collection of Metaphors

- E-Book: Metaphors – Stories that Heal the Soul

Introduction and Function

Introduction

Metaphors play an incredibly significant role in communication and personal understanding. For centuries, they have been used to teach and reshape ideas, beliefs, and attitudes toward life. Shamans, philosophers, and prophets intuitively recognized and harnessed the power inherent in metaphors. From Plato to Jesus, from Buddha to Don Juan, and even Richard Bandler, metaphors have been understood and used as powerful tools of influence.

In metaphors, people, animals, or plants face certain difficulties or unique situations. The metaphor tells the story of how they solved the problem or overcame the challenge. In doing so, we gain insight — and sometimes the metaphor “hits home” and inspires an idea about how we might resolve our own problems.

Function and Benefits

- The metaphor provides play material for the unconscious. The storyline keeps the left brain occupied while the message reaches the unconscious mind directly; the left hemisphere has no access to it.

- Metaphors can be effectively used in coaching, as they stimulate new perspectives and ways of thinking. The current issue is reframed in a new context and can be viewed with greater distance.

- Metaphors are often extremely helpful for integration. A dead end may dissolve through sudden insight — even if the metaphor simply translates information into a language the other half of the brain understands.

- Seminar participants find content far more relatable and memorable after hearing a story that illustrates it.

- Metaphors increase motivation and mood. They can be used to guide someone into a specific emotional state.

Important Principles of Metaphors

A) Pacing and Leading

Cameron-Bandler tells the following example, in which the client’s current experience and desired experience begin to blur, and pacing and leading flow seamlessly together:

“An attractive woman named Dot came for counseling. She wanted to learn to control her promiscuity and sought help for it. She was married to a good man (as she described him) and had two lovely children, but whenever and with whomever possible, she engaged in extramarital affairs. She wanted to stop this behavior.

I used the elements of her description to build a therapeutic metaphor. Like many attractive women, Dot was concerned about her slim figure (although she wasn’t overweight), so I used this theme to make the metaphor appear as a natural extension of our therapeutic interaction.”

Problem Description — Therapeutic Metaphor

This promiscuity leads her to lose her husband and self-respect.

A woman on the road to obesity. Dot cannot resist the temptation other men represent.

A woman who cannot resist desserts and rich foods when dining out.

Dot finds extramarital sex more exciting.

This woman loves eating out.

Dot is dissatisfied with sexual relations in her marriage.

This woman just picks at her homemade meals.

Each affair creates more guilt and brings her closer to losing her husband.

Each meal eaten out adds more fat.

Dot’s guilt becomes so painful that she must do something about it — she can’t sleep at night, and so on.

The overweight woman must do something about her habits — she no longer fits into her clothes.

Dot never developed satisfying sexual behavior with her husband.

The overweight woman never learned to cook something truly enjoyable for herself.

Up to this point, every element in the constructed metaphor is *isomorphic* (i.e., it has a one-to-one structural relationship) to the actual problem. The elements reflect the problem through their parallel form. The next step is to move from the mirroring of the problem to a behavioral-level solution.

The desired reaction the metaphor seeks is that Dot changes her behavior in a way that resolves the problem. The story must therefore lead to a behavioral change in the overweight woman who metaphorically represents Dot.

Dot should invest her energy in creating stimulating and satisfying sexual experiences with her husband.

The woman starts reorganizing her kitchen. She begins reading cookbooks, searching for suitable recipes, and experimenting with healthy and delicious meals.

Dot should find fulfillment at home.

Soon, faster than one might expect, she realizes that there’s nothing in restaurants that compares to her own creations — she no longer feels the need to overindulge elsewhere because she now finds satisfaction at home.

Dot is proud of her marriage and her sexual relationship with her husband.

Slim and confident, the once overweight woman is now proud of both her culinary skill and her trim figure.

People respond to such metaphors effortlessly. Something happens — but they often don’t even know exactly what.”

Metaphorical Solution

B) Double Induction

Double induction is characterized by one person receiving two simultaneous streams of verbal input — one or more metaphors, suggestions, or instructions — from two speakers. One speaker delivers input into the person’s right ear, the other into the left ear. The goal is to overload conscious perception, thereby allowing messages to pass directly into the unconscious mind. Each message is processed by the opposite hemisphere, creating different experiences in each half of the body.

C) Nested Stories

When depicting complex relationships or multi-step learning processes, the use of so-called “nested stories” (also known as “stacked realities” or “nested loops”) is particularly effective. The structure involves telling one story within another… and so on. The transition from one story to the next occurs at a moment of relative suspense in the current story.

Beginning

1. Start Story A

2. Start Story B

3. Start Story C

4. End Story C

5. End Story B

6. End Story A

7. End

Closing the stories works like drying freshly washed dishes — you dry the last plate you washed first. In the same way, the last story begun is the first to be completed.

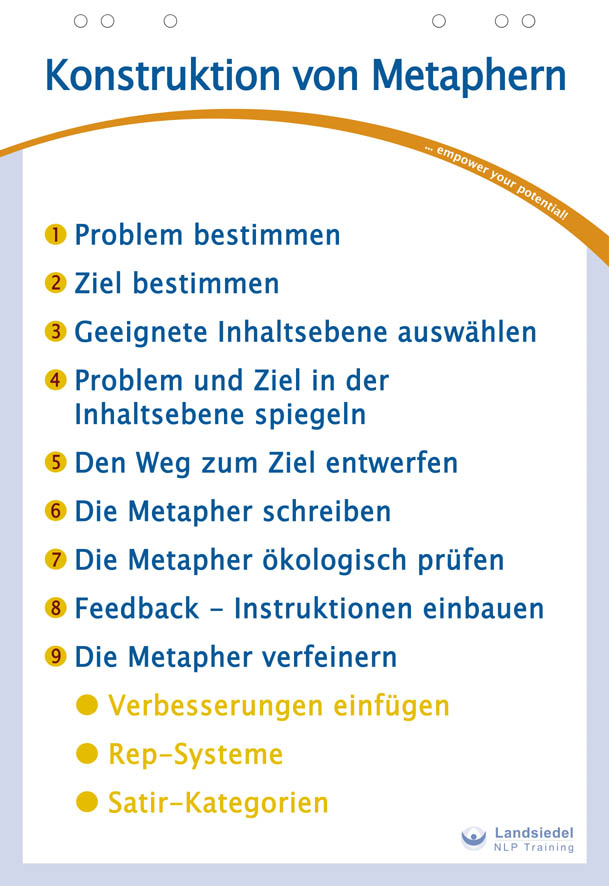

Construction of Metaphors

- Define the problem:

What is it about? Who are the relevant people? What roles do they play?

How does the main character act? How do others respond? etc.

Create a clear description of the problem. - Define the goal:

What does the person with the problem want to achieve? How do others respond to their behavior?

Write down the desired solution as well. - Choose an appropriate content level:

Find a symbolic or narrative realm that can mirror the structure of the problem, e.g. the world of gods, mythological realms, fairy tales with princes, princesses, magicians, witches, talking animals, plants and stones, or even figures from science fiction and history.

Important: The chosen context must be interesting and relevant to the person receiving the metaphor. - Reflect the problem and the goal within that level:

The story must structurally resemble the problem. A therapeutic metaphor always mirrors the structure of the client’s problematic situation, their relationships, and the problem context. Then the structures and processes that lead to the goal are mirrored in the story’s medium. - Design the path to the goal:

Introduce resources and build the sense that the client is capable of mastering the problem. Record this path in writing. - Write the metaphor:

Leave a blank line between sentences for clarity. - Check the metaphor ecologically:

Examine whether the intended goal fits harmoniously into a person’s life context without causing negative effects on their personality or social environment. Eliminate useless or harmful insights. Review the metaphor for potential misinterpretations or unwanted implications. - Add feedback instructions:

Include opportunities to provoke physiological responses that reveal whether the listener is following and engaging with the story. - Refine the metaphor:

- Add improvements and fine-tuning.

- Use NLP patterns to shape the journey toward the goal.

- Apply representation systems for pacing and leading:

Pacing the main representational system,

then leading into new systems to expand perception. - Use Satir categories for pacing and leading:

Placater, Blamer, Computer, Distractor.

Avoiding Misunderstandings in Metaphors

“A very competent woman who worked in a social therapy living community wanted a schizophrenic woman to spend more time in the common room to encourage more contact with others and less isolation. So she told her a story about a beautiful rose blooming in a shady, damp corner of a backyard. One day, the gardener noticed this rose, cut it, and placed it in a vase in the entrance hall, where everyone passing by could see and admire it…

The next day, the young woman cut her wrists to get attention (just as the gardener had cut the rose)!”

You can never completely prevent someone from finding an interpretation you didn’t intend — but you can make it harder for them to take the wrong path. Therefore, always check your metaphors for unintended meanings, ambiguities, presuppositions, and possible interpretations. Of course, a good metaphor also thrives on such layers of meaning.

Expressions like “kick the bucket” have two meanings — a literal one and one meaning “to die.” Every time such a phrase is used, both meanings register subconsciously.

Delivering Metaphors

Just as important as constructing a metaphor is the way it’s ultimately delivered. Establishing optimal rapport is crucial. In group settings, try to pace the three main representational systems.

- Deliver congruently

- Hide your intention (pretend the story is about someone else)

- Decide whether to use trance (often better for deeper anchoring)

- Observe unconscious feedback

- Do not interpret the story afterward

Sources for Metaphors

- Bandler and Grinder recommend professional journals

- Animal fables

- Children’s fairy tales (Grimm’s Fairy Tales, 1001 Nights, etc.)

- Sufi stories

- The Bible and other religious texts

- Online collections

- Science fiction

- Historical metaphors (Hannibal, Caesar, Henry VIII, etc.)

Exercise for Developing Metaphors

- Person A identifies a state they wish to change and defines a desired state they want to reach instead.

- Person B asks A about the current state using the list: “If this state, problem, or feeling were a kind of ... (e.g., landscape) ... what would it be like?” Find five to ten or more metaphors for this state, then repeat the same process for the target state.

- Person B then creates a story using the collected metaphors, starting with the current situation and gradually guiding the narrative into the desired state.

The transition from one state to another can happen in many ways:

- a flying carpet

- the main character boards an airplane

- they dream a dream

- another person appears and tells a story, etc.

Worksheet for Developing Metaphors

If this state were a ... what would it be?

Landscape

Color

Fairy Tale

Idol/Hero

Vehicle

Beverage

Temperature

Sound

Music

Taste

Bird

Plant

Weather

Animal

Symbols for Metaphors

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Abyss | Fear of falling or failure |

| Harbor | Arrival, home, safety |

| House | Security, symbol of the person and their current state |

| Insects, Maggots | Something is rotten; Flies: something is annoying; Butterfly: transformation; Bees: diligence |

| Juggler | Joy in doing several things well and elegantly at once |

| Cactus | Fear of contact or being touched |

| Circle | Perfection, complete harmony |

| Teacher | Inner guide or counselor |

| Lily | Rebirth, transformation |

| Magician | Someone with the power to transform their inner world |

| Magnet | What attracts or draws us |

| Nakedness | Vulnerability, openness, sensuality |

| Fog | Something hidden, slow progress |

| Oven | Incubating an idea, rest |

| Oil | Kindling fire, calming the waves |

| Package | Letting go of something |

| Perfume | Sensuality, lack of self-control, feeling victimized |

| Puzzle | Lack of clarity, missing pieces |

| Pyramid | New level of consciousness |

| Rainbow | Pot of gold, completion, fulfillment |

| Journey | Change and growth |

| Shadow | Untapped potential, hidden positive intent |

| Ship | Person within their emotions |

| Dancing | Lack of self-control, being caught in emotion |

| Tunnel | Limitation, altered state, inner path to oneself |

| Weather | Emotional state |

| Meadow | Balance, connection with nature |

| Room | An aspect of the self |

E-Book: Metaphors – Stories that Heal the Soul

Enjoy reading and experimenting! Best wishes from author Stefie Rapp and publisher Stephan Landsiedel.

Free E-Book

Metaphors

Stories that Heal the Soul

In this e-book, you will learn:

- Why metaphors can heal the soul

- How to use metaphors in coaching, conflict resolution, training, public speaking, consulting, and parenting

- How to construct a metaphor – step by step

In this e-book, you will learn:

- Why Metaphors Heal the Soul

- The Truth about Metaphors

- Why Metaphors are so Powerful

- How to Use Metaphors

- How to Construct a Metaphor – Step by Step

- Tips for Presenting Metaphors in Training

Enjoy reading and experimenting! – Author: Stefie Rapp, Publisher: Stephan Landsiedel

During my NLP Master training, I consciously encountered the topic of “metaphor” for the first time. Fascinated from the very first moment, I developed a love for it that continues to this day.

Why Metaphors?

When I delved deeper into the subject, I realized how effective and transformative metaphors can be. Since then, I have used them daily in my professional work: in training, to illustrate concepts; in individual coaching, to create symbolic solutions; and in communication or mediation, to help others discover their own “truth.” Now I would like to share these insights with you and give you tools to develop fitting metaphors quickly and creatively.

The Truth about Metaphors

“Truth knocked at the door of humankind,

but no one let her in, for she was naked.

Parable found Truth alone and shivering,

took her home,

and clothed her in a story.

When Truth knocked again,

the people opened their doors

and sat together by the fire till late at night.”

(Author unknown)

This chapter is like visiting a garden center filled with seeds. You can choose which ones to plant — and it’s up to you whether they take root and bear fruit, or wither away forgotten.

Meaning:

“Metaphor” literally means “a transferred, figurative expression.” The word comes from the Greek metaphorá, meaning “to carry over” or “transference.”

Example:

Trust is like a beautiful porcelain cup. Once it falls and breaks, it may be glued back together, and you can still drink from it — but it will never be quite as beautiful as before. This metaphor helped me explain to my seven-year-old son how important it is to tell the truth, as otherwise the “trust” between us changes.

Why Are Metaphors Such a Powerful Tool in Communication?

- They offer people an interpretation of what truth might be.

- They present solutions gently, without overwhelming.

- They illustrate ideas, people, and experiences vividly.

Every metaphor conveys meaning — deepening our understanding. It tells a story that may consist of a single word or phrase. Metaphors reveal how others perceive reality. And if we fail to understand them, they may even end up thinking for us.

Many people encounter a metaphor at some point in life that profoundly moves them or stays with them for years.

Stories touch us. Stories heal.

References

Story Power (Vera F. Birkenbihl)

Metaphors – Workbook (Alexa Mohl)

Duck or Eagle (Ardeschyr Hagmaier)

The Story Theater Method (Doug Stevenson)

Deutsch

Deutsch English

English Français

Français 中文

中文 Español

Español नहीं

नहीं Русский

Русский